How random is random? (The Truth About Spotify’s Shuffle Button)

For the average person, this question should seem somewhat useless. A fact that happens without much explanation or relation to a previous circumstance, and that we sometimes like to attribute to chance, fate or coincidence. On the contrary, for music lovers like me who listen to more than 50,000 minutes of music a year and regularly seek fresh sounds, this question is no small matter. How random is random?

When you dedicate so many hours a year to curating your music playlists by genre, year or musical trend, it’s really important to know that when you select the “shuffle” or “random play” option on Spotify, you’re receiving exactly what you’re looking for: a frenetic and unpredictable sequence of songs that lifts you several feet off the ground and will never repeat itself. A unique, surprising and special continuous thread of hits that tomorrow or the day after won’t be the same: almost like turning on a radio that only broadcasts our favorite songs in no particular order. Because random is precisely that: random. Or am I wrong?

When “Random” isn’t enough

It was 2014 and a group of engineers at Spotify seemed as convinced as I was about this last statement. The random experience on their platform was guaranteed since “shuffle or random” mode was supported by an algorithm programmed precisely to achieve that effect: play the next song with the same uncertainty and excitement generated by flipping a coin in the air. However, they were greatly surprised to learn that a large number of recurring platform users kept insisting that the “shuffle” functionality had flaws and wasn’t “random” enough for them.

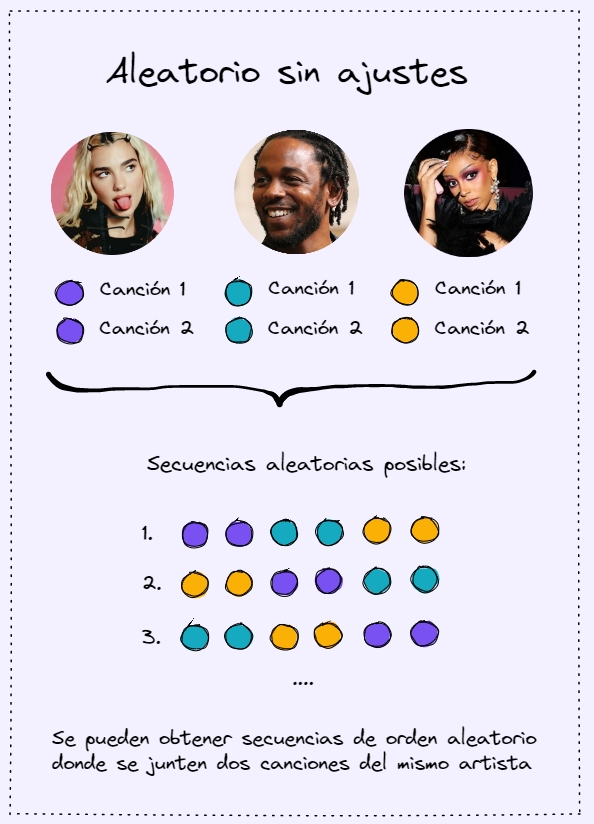

Fortunately for the streaming giant, Lukáš Poláček, a part-time employee and still a Computer Science student in Stockholm, often passed by the same meeting room where this group of engineers sat debating frequent user pain points and planning upcoming improvements. One fine day, right in the same season Lukáš was reviewing Random Algorithm Theory, he decided to offer them help. After analyzing the case in detail, it only took Poláček one day of work and 15 lines of code to find the solution to the “problem.” The effect was immediate. Spotify’s hardcore users raised their virtual glasses in sync as a symbol of approval. The part-time employee had done it.

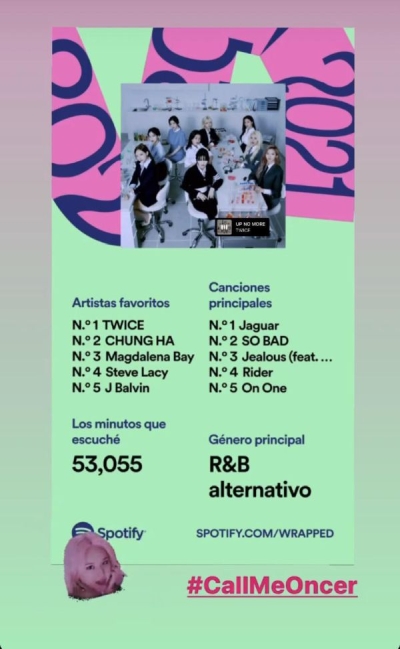

“Mr. Shuffle,” as he was later called at Spotify parties, simply rewrote the algorithm so that songs by the same artist were distributed more or less evenly throughout a playlist. An example can help explain it better. Imagine that in the same playlist you have two songs each from Dua Lipa, Doja Cat and Kendrick Lamar, respectively. Prior to Poláček’s correction, as a user choosing “random mode,” it’s perfectly possible you’d get a song sequence where you hear two songs by the same artist back to back. This is randomness in its “pure” state.

However, after the algorithm change, songs are distributed better and only sequences are allowed where two songs by the same artist don’t play consecutively. That is, the algorithm creates a “random” sequence tailored to the human brain.

We might be tempted to think this user problem found by Spotify engineers is an atypical case, but the truth is this company hasn’t been the only victim of its clients’ whimsical perception. Years earlier, during the golden age of the iPod, many device users complained about receiving their player with defects, especially because its “shuffle” button wasn’t random or unpredictable enough for them. Sound familiar? Steve Jobs quickly understood what was happening and in an official 2015 product keynote, the guru asserted with full confidence: “[the shuffle button] is truly random, even though this means sometimes you’ll hear two songs by the same artist, one next to the other.” Despite this explanation, Jobs and his engineering team would eventually design the “Smart Shuffle” functionality, which allowed users to define how many songs by the same artist or from the same album they were willing to hear consecutively.

Are humans weird?

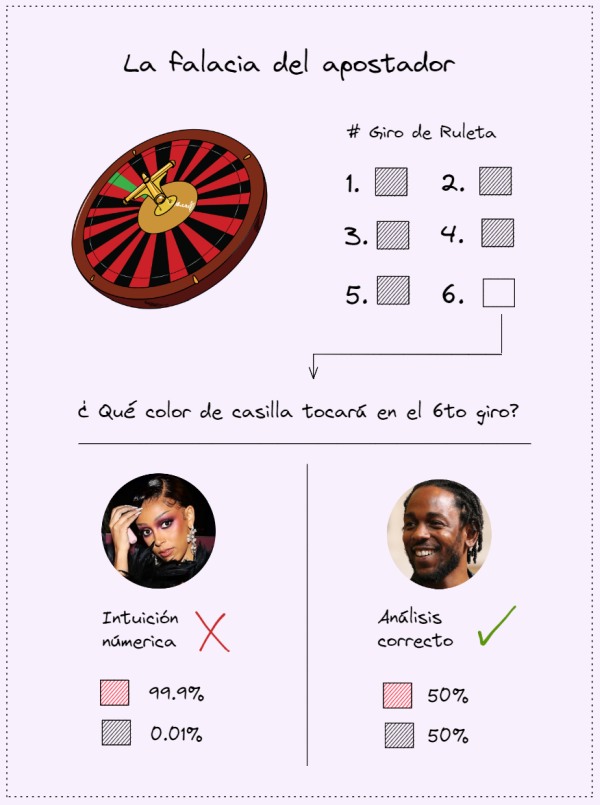

The way our brain perceives what’s “random” doesn’t exactly match how it actually works. This phenomenon is observed so repeatedly in human behavior that numerous studies have been conducted on it and experts even define it with a name: “the gambler’s fallacy” or “the Monte Carlo fallacy.” Indeed, this cognitive bias can be defined as “the incorrect belief that if an event happens very frequently in the past it’s less likely to happen in the future (and vice versa), when it’s been established that the probabilities of each event are independent.”

Again, let’s go with an example to make it clearer. Imagine you’ve sat down at the Roulette game in your city’s most popular casino and your task is to bet on red or black spaces. They inform you that “black” has just come up for the fifth time and now invite you to bet. Do you choose black again or choose red? Your logical sense will offer you a quick decision and you’ll believe that after a streak of “blacks,” there’s a high probability the next space will indeed be “red.” In a matter of seconds, the game’s adrenaline will have made you forget a big detail: each play is independent and each color has the same probability of winning: 50% for black and 50% for red. Bingo! It’s complete chance.

Everything seems to indicate that human judgment or intuition could be as damaged as Spotify’s “shuffle” button in 2014, don’t you think? And it’s that sometimes the human being’s strange obsession with finding patterns where there simply aren’t any can quickly lead them to error. In the words of Michael Shermer, main columnist for Scientific American and author of various bestsellers, “[humans] evolved in what’s called ‘Middle Earth’ […] in that Earth, our senses evolved to perceive medium-sized objects […] they’re not equipped to perceive atoms or germs on one side of the scale with the naked eye, or galaxies or the universe on the other. We evolved to understand the world at medium scale.” In that same sense, Shermer adds “in this Middle Earth, our numerical intuition leads us to pay attention to and remember short-term trends, meaningful coincidences and personal anecdotes” overlooking the real probabilities of something actually happening.

The same senses that prevent us from perceiving elements passing at the speed of light and prevent us from witnessing the slow movement of continental plates over time are the same ones that lead us to believe Spotify’s “random” mode isn’t “random” enough and (sometimes) to lose a lot of money at casinos. Shermer adds, “although our intuitions can be very useful for dealing with other people and developing social relationships (key elements in the evolutionary history of a primate species like ours), these same intuitions lead us to error when we have to face probabilistic problems.”

Apparently “random” is frequently a whimsical interpretation by our brain and is far from what should actually be considered as such. Either way, I’m sure that after reading this article, your intuition won’t fool you so easily again.